How Does Scarcity Guide Our Attention?

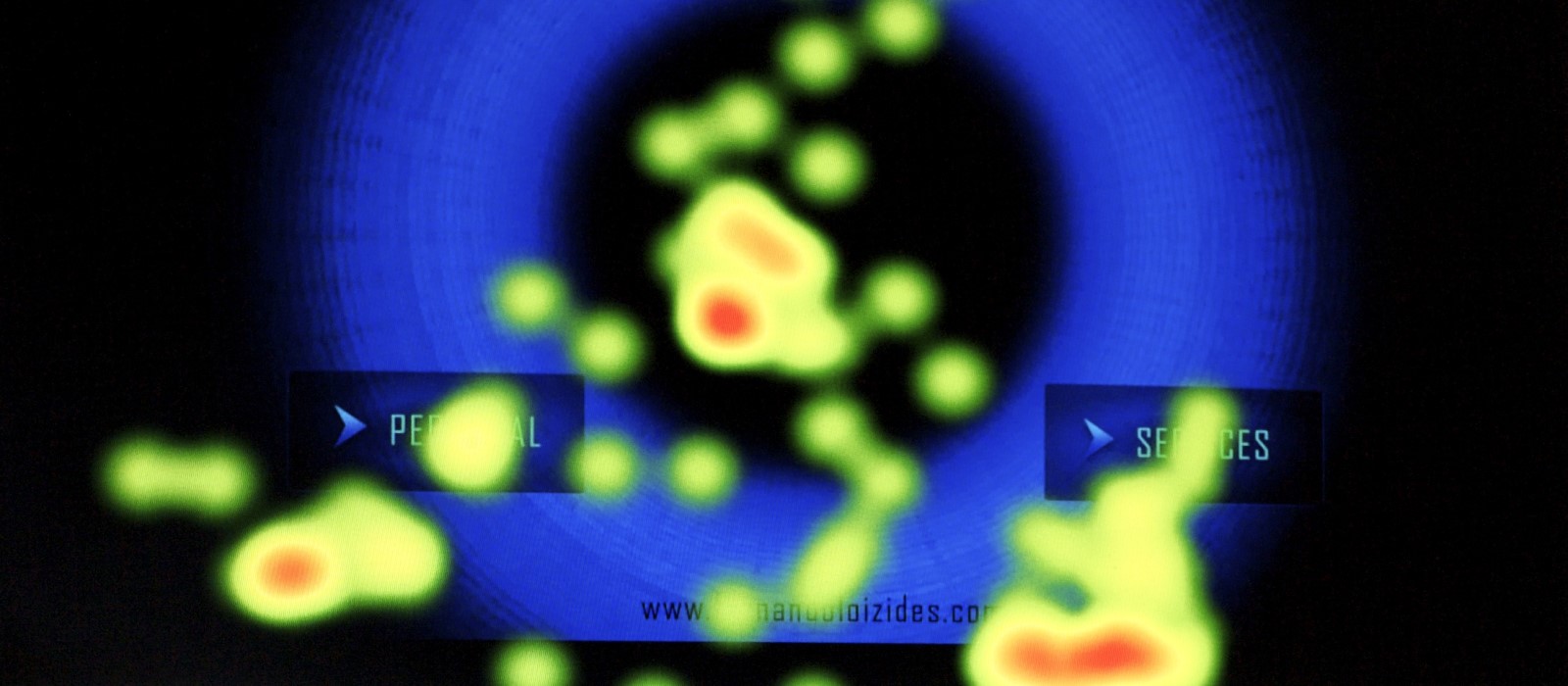

Eye tracking demonstration | City University Interaction Lab via Flickr

Study Context

Why do people living in poverty often demonstrate behaviors that perpetuate poverty? One recent account (Shah et al. 2012) proposes that scarcity (including financial scarcity) changes how people allocate attention, leading to greater focus on the scarce resource itself at the cost of attention to other information. This phenomenon has been dubbed the “tunneling effect”. In their influential study, Shah et al. (2012) ostensibly demonstrated both the positive and negative effects of tunneling. In a video game, “poor” participants, who were endowed with fewer shots to clear targets, used their shots more efficiently than “rich” participants. However, poor participants also frequently borrowed shots from future rounds at high interest rates, which rich participants did not. According to the tunneling account, poor participants failed to realize how counterproductive their borrowing was because they were so focused on using their shots efficiently. This study provides a re-analysis of Shah et al. 2012 (Study 1) and an online experiment reinterpreting the notion of tunneling in the literature on scarcity (Study 2).

Study Design

Study 1 reanalyzed the data from the original study of Shah et al. (2012) and their replication (Shah et al., 2019), which are publicly available online. Study 2 uses an adapted version of the “Angry Blueberry” game, used in prior studies (including Shah et al. 2012) investigating the tunneling effect created by scarcity. This adapted version of the game is specifically designed such that it allows us to measure behavioral effects (e.g., efficiency in dealing with resources). The study aimed to further validate the experimental paradigm by testing it with a sample of 174 online participants via Amazon’s MTurk.

Results and Policy Lessons

In Study 1, the researchers show that although “poor” participants borrowed more shots from future rounds than “rich” participants in absolute terms, this was because poor participants were far more likely to encounter situations in which they could borrow. When analyzing borrowing behavior in relative terms, poor participants actually borrowed less frequently than rich participants. In Study 2, the researchers adapted Shah et al.’s task but held the frequency with which poor and rich participants faced economic decisions outside of the “attentional tunnel” constant. The researchers found that under these conditions, scarcity led to greater focus, but crucially, this did not come at a cost. In contrast, poor participants were actually more rational in their decision-making than rich. Together, these studies open new questions into whether poverty-reinforcing behaviors, like overborrowing, can be explained by attentional neglect.

To find out more about this project, see the video below: