Technology Is Not a Panacea, but It Can Help Solve Specific Problems

On September 28, CEGA hosted its annual Evidence to Action (E2A) conference, this year titled “Realigning Tech for Social Impact.” It brought together researchers, policymakers, practitioners, funders, community members, and students to take stock of the benefits and harms technological interventions have had over the last two decades, with an emphasis on the experience of communities in low- and middle-income countries. Sean Luna McAdams, program manager for the Data Science for Development portfolio, shares key takeaways from the event.

New technology benefits from a simple and powerful narrative: it can help solve complex problems, often by doing more with less. The printing press accelerated our ability to share information over long distances. Social media has made it nearly costless to communicate with anyone, anywhere in the world. But new technologies can have unintended effects. The cotton gin turbocharged an economic model that relied on enslaved African labor and ill-gotten land, with terrible consequences. More than one account at E2A emphasized this nuance of the effects of technological interventions.

Over the course of the day, participants surfaced a set of complementary best practices when designing, testing, and integrating tech into existing policy, governance, and social welfare systems. The first speaks to the limits of expertise: a technically excellent product is necessary but not sufficient for social impact. Additionally, the ultimate goal of scaling a solution is often underspecified. Scaled by whom, for which communities, and at what scale (national, regional, global)? Making these answers explicit can improve estimates of the trade-offs to scaling and ensure the technological solution is the right fit for its intended problem.

Beyond Technical Excellence

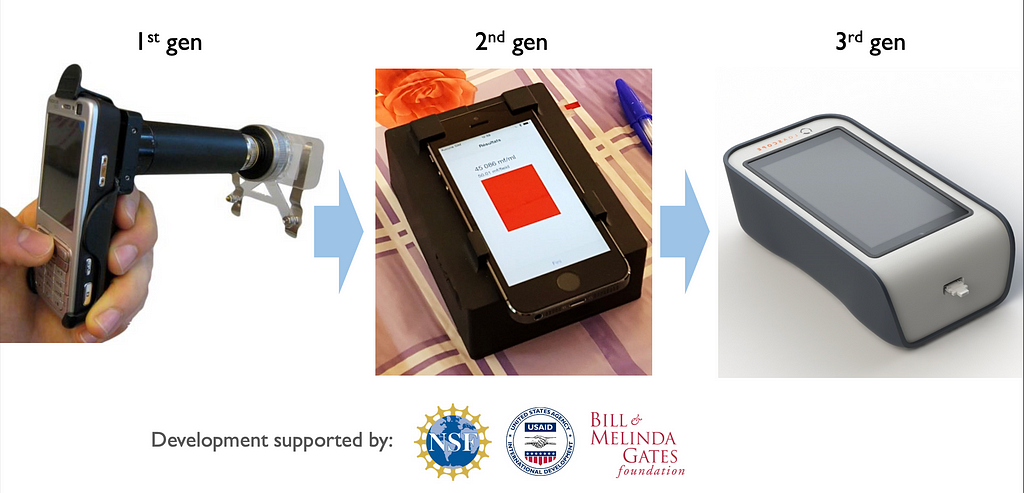

At E2A, the best examples of technology improving lives and achieving large-scale adoption in low- and middle-income countries relied on interdisciplinary teams, incorporated community input, and planned for maintenance and capacity building to ensure sustainability. Interventions developed with these elements can cultivate community trust, clarify their value proposition for potential users, and dynamically adapt and improve their product. Dan Fletcher, Professor of Bioengineering and Faculty Director at the Blum Center at UC Berkeley, reflected that the initial prototype of Cellscope failed during field testing despite its technical excellence because it was developed only by engineers. Subsequent iterations involved experts from the social sciences, improving the product and leading to greater success.

However challenging, collaboration across disciplines is essential for successful interventions. Mohamed Abdel-Kader, Chief Innovation Officer and Executive Director for the Innovation, Technology, and Research (ITR) Hub at USAID, reminded us of the value of proactively including people “whose lived experience can provide different perspectives.” For USAID, this means ensuring that 25 percent of its funding is dispersed to local organizations. Daanish Masood, Advisor on AI Alignment at the UN’s Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs, echoed this call by highlighting the importance of “epistemological pluralism” to more effectively engage community members who often perceive and value their world using different frameworks. By bringing together multidisciplinary teams, innovators can develop technologies that will better meet the social reality in which they will be deployed.

Not only does diversity make technology more effective, it also helps to minimize potential harm. For example, Josh Blumenstock shared how his team gathered input from rural communities in Togo to inform the development of a social transfer targeting software his team co-created with the Ministry of Digital Economy and Transformation. Zoe Kahn, a PhD student on Blumenstock’s team in Togo, conducted ethnographic research to better understand how members of rural communities would interact, understand, and appraise the digital social transfer system they were building.

Finally, technically excellent solutions must build the social consensus and requisite buy-in across different contexts to tailor and maintain these tools iteratively. This requires planning for the long-term, building in plans for deprecation, and creating institutions — whether private companies, volunteer-based organizations, or capacity-building initiatives — to maintain and update these innovations to make them sustainable over the long-run.

What Does Success Look Like?

We should not assume that we have the same vision of a successful technological innovation in the social impact space. We often tout “scaling” as the final life stage of tech; for many, it serves as the ultimate goal and proxy of success. Yet, Brigitte Hoyer Gosselink, Director of Product Impact at Google.org, distinguished two paths to integrating technological interventions: a tailored, individualized solution in close partnership with a decision maker and centralized, replicable systems that can be deployed across time and space reliably.

Should a technological intervention in global development be global in scope? We need a better sense of the trade-offs in scaling up from local to global to answer this question empirically. Some systems may be better suited to function at national or regional scales. Collaborators should plan to measure performance reliably across scale to tailor solutions accordingly.

As Jane Munga, Fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, reminded us: even if we develop good tech solutions for citizens who have a mobile phone and access to the internet now, there is a sizable portion of the world’s most underserved who would be excluded due to lack of access. We need to expand the size of the pie, improve the quality of its ingredients, and increase the diversity of the culinary team that bakes it. Digital technology has a role to play in achieving more equitable social and economic development world-wide. How transformative that development will be depends on us.

Technology Is Not a Panacea, but It Can Help Solve Specific Problems was originally published in CEGA on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.